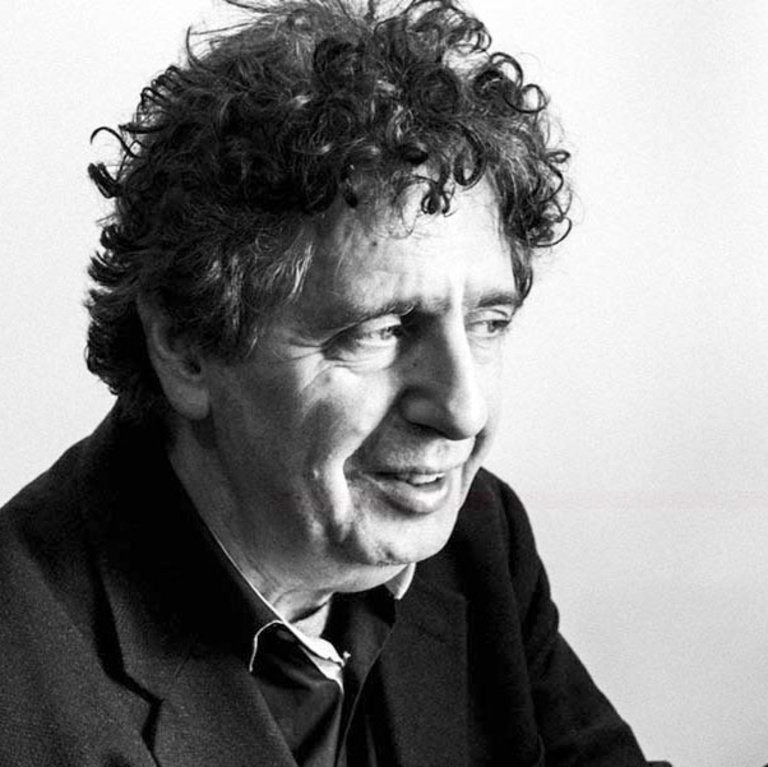

Interview with Michaël Levinas

COMPOSING A PASSION AFTER AUSCHWITZ

In accepting this commission, I decided to borrow Emmanuel Levinas's dedication to Autrement qu'être, a work in which he speaks of a passivity more passive than passivity, of a radical exposure to the otherness of others, of a denudation, of a sacrifice. This dedication expresses what was for me the starting point and the spirit in which I worked from the beginning on this Passion according to Mark. A Passion after Auschwitz, a work that also confronted me with my own history: "To the memory of those closest to me among the six million murdered by the National Socialists, alongside the millions and millions of humans of all faiths and nations, victims of the same hatred of the other, of the same anti-Semitism."

A strictly musical and in no way theological formal unity

This Passion according to Mark. A Passion after Auschwitz could evoke an altarpiece, a triptych: Jewish prayers for the millions of dead of the Holocaust, the Gospel according to Mark in Old French from the 13th century, and two poems by Paul Celan. The music of this Passion is a meditation on what undoubtedly connects the two religious traditions—Judaism and Christianity1—but also on this irreparable loss, these six million dead of the Holocaust, the silence of God and that of men. I chose the texts and the layout. The whole piece is composed of traditional Jewish prayers in Aramaic and Hebrew (Kaddish, El Maleh Rahamim) and the names of the victims of the Holocaust for the first part, and the poems Die Schleuse and Espenbaum by Paul Celan for the third part. They frame the second part, chapters 14 and 15 of the Gospel according to Mark in 13th-century French, according to the manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale.

How were the musical unity and form of this Passion according to Mark formed? A Passion after Auschwitz?

In this Passion written in the 21st century—this Passion after Auschwitz—there are issues that clearly and inevitably refer to the foundations of Bach's masterpieces. I am thinking primarily of the highly complex and non-theatrical relationship that exists in a Passion between narrative and action in a religious ceremony that sings the great sacred texts, the choice of languages to sing these texts, musical narrative and its forms, polyphony, particularly that resulting from the communion of the faithful, and the sense of time in the liturgy.

The succession of episodes, motifs, and passage

The succession of episodes from the Gospel, but also of prayers and implorations, forms a narrative writing that alternates between narrative and action. This is a characteristic of a Passion. Formal unity is created by motifs, figuralisms, and symbols that gradually metamorphose. I can mention some of these sung motifs that also allow the passages from one episode to another, from a prayer to a story, the musical link between the two religious traditions, the constitution of the great form and the melody. I will cite the hammered punctuations of the Kaddish, which are transformed into the sound of the nails of the crucifixion; the tears, the shouted words in El Maleh Rahamim and the strange third of Yizkor, which becomes the central interval of Paul Celan's poems; the imploration of the mother which becomes the theme on the cross, which is transformed into the theme of betrayal; the canticle of Bethany, which becomes that of the ascension of Jesus; the clamors of El Maleh Rahamim, which take the form of a polyphony with the rhythms of the Kaddish and the bells for the crucifixion.

As I have indicated, the symbolism of all motifs gradually transforms, like the motifs themselves: the transition from one episode to another. Passage is an essential musical parameter in the history of forms up to the present day, whether or not there is a relationship to a text or an allegorical narrative. It is one of the foundations of musical time. It undoubtedly plays an essential role in Bach, Beethoven, and Wagner. As in my operas, passage determines the musical writing and the establishment of the text, the organization of modal and tonal scales, and their progressive alterations; modulations follow the syntax of languages and the time of the narrative. Passage is at the origin of the intervallic, harmonic, orchestral, and symbolic metamorphoses that constitute the unity of this Passion on a strictly musical level.

The polyphony of the rumors of prayer

Whether in the Jewish part (the Kaddish, the Ashkenazi synagogue rumors, the El Maleh Rahamim, etc.) or in the Christian part (the implorations of Mary, the canticles of Bethany, etc.), the choirs are written in 36 separate voices, mixing spoken rhythms, the details of the words (consonants). This almost Lettrist listening to languages is found in the orchestration. For the first part, Jewish, I developed a listening to the synagogal polyphonic specificities of the prayers said, in this language disrupted by tears and tragic accents, that in force in the Ashkenazi pronunciation, the language of all those who perished in the camps. In my reading of chapters 14 and 15 of the Gospel according to Mark, I felt a very great violence, not only between Jesus, the turba and his judges, but also in the relationship with the disciples. Thirteenth-century French and sentence structure seek to convey this evangelical dissonance.

Celan: breath and trembling

My music has always been marked by the breath of flutes, by what I call the "rustling of wings," the breathlessness of the voice. Trembling! The vocal essence of the musical of sound, the beyond of timbre, is trembling. It is in this trembling that the despair of Paul Celan's poem is expressed. It is the German language that keeps in memory the Yiddish and Hebrew of the shtetl synagogue: the tragic and despairing third of Yizkor. It is this same despair after Auschwitz (the third of El Maleh Rahamim) that punctuates and brutally interrupts Die Schleuse. Paul Celan rediscovered a word that "me" was looking for, and not that the poet was looking for: "Kaddish." Then through the lock, he had to pass to save the word: "Yizkor!" [Remember]. Paul Celan's language always weeps. It screams, it trembles. It's Espenbaum. The mother will never return, and she will never have gray hair. The son mourns the mother who will never return. I agreed to write this Passion According to Mark. A Passion after Auschwitz. Why after Auschwitz? Writing music after Auschwitz means composing music that trembles. It means constantly asking the same question that haunted Paul Celan. Can we sing without crying and without trembling after the Holocaust? The question will always be asked.

Michaël Levinas

Excerpt from an interview conducted by Danielle Cohen-Levinas published by Éditions Beauchesne (Paris, 2017)