Accueil

Prochains concertsProchains concertsProchains concertsProchains concertsProchains concertsProchains concerts

4 — 5 févr. 26

To Be Sung

opéra • Pascal Dusapin | Pharrell Williams

Fondation Louis Vuitton

Paris

Paris

30 janv. — 1 févr. 26

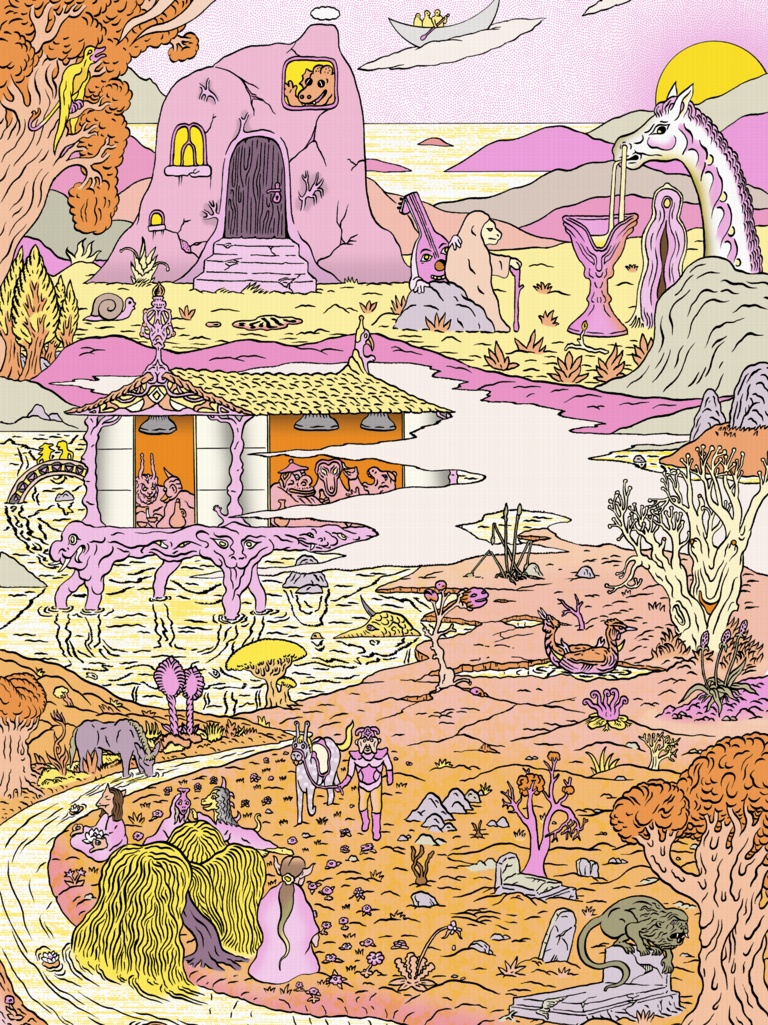

La Planète Sauvage

ciné-concert • Goraguer | Hershkovits | Louati

Philharmonie de Paris - Cité de la Musique

Paris

Paris

29 mars — 3 avr. 26

I Didn't Know Where To Put All My Tears / Curlew River

Nikodijević | Britten

Opéra national de Lorraine

Nancy

Nancy

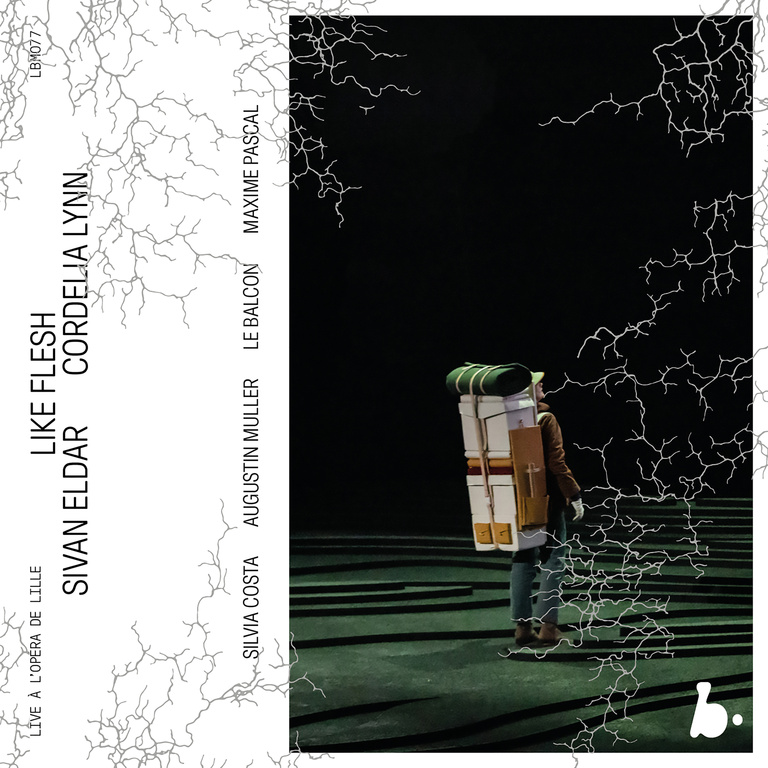

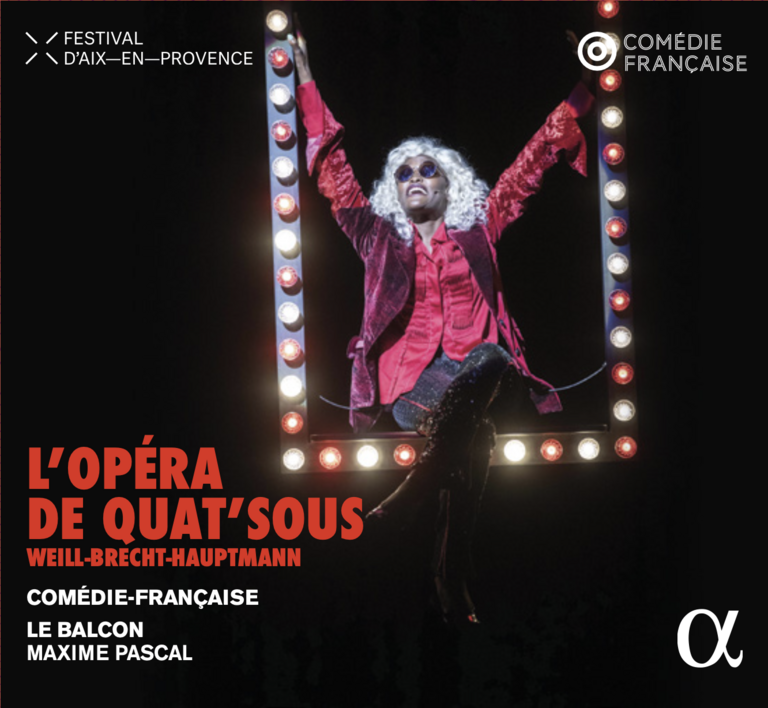

Le Balcon tire son nom de la pièce de Jean Genet (Le Balcon, 1956), situant son engagement artistique à l’endroit du récit, de la parole et de la représentation.

À la uneÀ la uneÀ la uneÀ la uneÀ la uneÀ la une

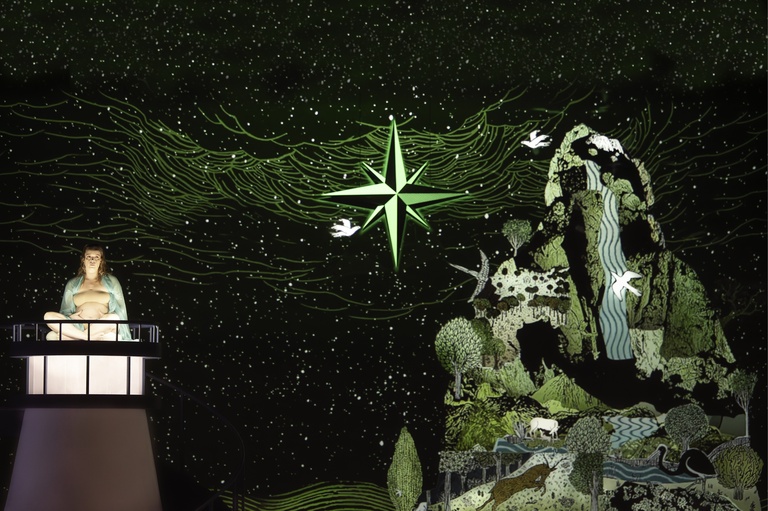

Montag aus Licht

Opéra de Karlheinz Stockhausen

Sixième "Journée" de notre intégrale Licht

Le 29 novembre 2025 à la Philharmonie de Paris

Photo © Hervé Escario

ActualitésActualitésActualitésActualitésActualitésActualités

Hommage à Pierre Boulez

Le 19 août, Le Balcon s'est rendu au Festival de Salzbourg pour un concert-hommage à Pierre Boulez. Explosante-Fixe et Sur Incises y ont dialogué avec des pièces de Karlheinz Stockhausen et Luigi Nono.

ProductionsProductionsProductionsProductionsProductionsProductions